INTRODUCTION

Tobacco causes more than 8 million deaths each year worldwide from long-term first hand and secondhand effects of cigarette smoking1. Smoking is the act of inhaling and exhaling the fumes of burning plant material. A variety of plant materials are smoked but the act is most commonly associated with tobacco smoked in cigarettes2. It is reported that 80% of the total population of smokers worldwide are in low- and middle-income countries3. Despite this, smokers in poor countries had no less interest in quitting smoking4. Smoking cessation treatment is a vital element in the MPOWER (Monitor tobacco use; Protect people from tobacco smoke; Offer help to quit tobacco use; Warn about dangers of tobacco; Enforce bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship; Raise taxes on tobacco) package of tobacco control measures recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). Most tobacco users want to quit, but only a handful receive support and help to overcome their dependence and the healthcare systems are responsible for treating tobacco dependence. Programs provided by the healthcare system must include tobacco cessation advice, access to medicine, and quitline5.

Stopping smoking leads to immediate and long-term benefits such as reduction of risk of stroke among high-risk patients6 and premature cardiac deaths among patients7,8. The global prevalence of current male smokers is 25% with half of the smokers from Asian countries (China, India, Indonesia). The economic cost of smoking is at a staggering US$ 2 trillion, as most of the cost involves loss of productivity due to smoking-related disease9. This amount has not included other collateral damages such as secondhand smoking, agricultural loss of biodiversity, soil erosion, and fire hazards10. ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries have approximately 122.4 million smokers, which is equivalent to 10% of total smokers worldwide11. Indonesia has the highest number of smokers in Asian countries11. Asian countries are the major contributors of the total number of smokers worldwide. The number of male smokers is much higher than female smokers. In 2019, according to a study by Yang et al.5,9,12, the global prevalence of current smoking in men was 25%, and nearly half of the smokers were from China, India, and Indonesia. Among the Asian countries, Indonesia has the highest prevalence of male smokers (76%) followed by Laos (57%), China (48%), Vietnam (47%), Cambodia (44%), Malaysia (43%), Philippines (43%), Pakistan (42%), Thailand (41%), Bangladesh (40%), Nepal (37%), Japan (34%), Myanmar (32%), Singapore (28%), Sri Lanka (28%), South Korea (22%), and India (20%).

A total of about 1.3 billion cigarettes are smoked every day in ASEAN countries. High-income Asian countries like Japan and South Korea have a similar smoking prevalence compared to other developed countries such as Germany. The overall prevalence of smoking in Japan is 19.3%13, with predominantly male smokers (26.6%) while 9.3% are female smokers11. The overall prevalence of smokers in South Korea with predominantly male smokers did not differ dramatically compared to Japan (19.9% vs 19.3%).

In accordance to the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) Article 14, governments should make smoking cessation easily accessible for would-be quitters. Unfortunately, only a quarter of the 181 WHO FCTC signatories have designated budgets for smoking cessation14. Tobacco control interventions have had a positive outcome in high-income Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea and Singapore, but the results have not been replicated in low- and middle-income countries such as China and India15. Smoking cessation services in Asian countries vary widely, from almost none, to quit advice at healthcare facilities, to brief intervention, and counselling with pharmacotherapy. In some countries, private pharmacies provide advice on how to quit smoking and in others, telephone quitlines are available16. Health workers who have undergone training for smoking cessation are more likely to provide smoking cessation counselling for their patients17. People who receive counselling are more likely to quit smoking compared to minimal intervention18. Pharmacotherapy, such as nicotine replacement therapy and varenicline, for smoking cessation helps smokers to overcome withdrawal symptoms during the smoking abstinence period, and is of proven effectiveness19. It has been estimated that simply providing nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) with the effectiveness of even 1% above baseline in low- and middle-income countries could save nearly 3 million lives over the next century20. However, uptake of NRT is low as it is too expensive for many smokers in poor Asian countries, and even when subsidized the uptake of NRT is low19. Asian cultures are typically collective and family centered. Hence, group-based social support techniques such as family therapy or ‘buddy’ systems may be of greater interest to smokers than individual treatment21. Group-based interventions offer patients the opportunity for social learning, for example sharing knowledge and skills about behavioral techniques for smoking cessation, generate emotional experiences and provide mutual support22. Evidence has also shown that group therapy for smoking cessation had demonstrated preliminary efficacy and feasibility of group-based smoking cessation treatment with pharmacotherapy in a special population23.

Furthermore, group-based approaches may be a more efficient way of reaching and supporting the many millions of Asian smokers who need support to quit than current individually targeted approaches. In some settings, group treatment has been shown to be more effective than no intervention or minimal intervention and about as effective as an intensive individual intervention24 but more affordable25. In this systematic review, our objective was to examine the evidence on the availability of group therapy as a behavioral intervention for smoking cessation for smokers who want to quit smoking in Asian countries and the documented abstinence after a quit attempt.

METHODS

We conceptualized the review by setting various objectives related to the subject of behavioral support, particularly group therapy, in Asian countries. The objectives were to determine the abstinence rate among patients in group therapy as a behavioral intervention for smoking cessation and to compare the effectiveness of group-based therapy for smoking cessation available for smokers to quit smoking in Asian countries. Abstinence is defined as no use of combustible cigarettes, without considering the use of other tobacco or alternative products26 and not smoking for 3 to 6 months from the quit date. The study population in this systematic review are smokers who have joined a group therapy as a behavioral intervention for smoking cessation conducted in Asian countries with abstinence from smoking as the outcome of interest.

The behavioral intervention has been frequently used to help smokers to quit smoking but the effectiveness and content of the intervention vary substantially. To identify the eligibility of the studies included in the systematic review, we searched and reviewed the articles with the keywords: ‘smoking’, ‘cigarette’, ‘tobacco’, ‘nicotine’, ‘group therapy’, and ‘cessation’ (smok*, *cigarette*, tobacco, nicotine, group therap*, cessation). We selected studies to be included in this systematic review based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The key criteria used during the assessment of the type of study selected in this systematic review were: recruitment, treatment allocation, randomization, response rate, outcome measurement, levels of missing data, and how missing data were addressed. In our systematic review, studies with participants who were cigarette smokers aged ≥18 years, articles from 1 January 2004 to 6 July 2020 published in English only were included. The databases searched were PubMed, OVID Medline, SCOPUS, Google Scholar and PsycINFO. We also looked if the reported smoking cessation abstinence measurement of cessation used biochemical validation at the reported time point. Studies with incomplete data or estimates were excluded from the analysis. Studies with low grade of evidence were included only after discussion among the researchers. A third reviewer was consulted when an agreement could not be reached between the two researchers. Various study designs including systematic reviews, qualitative studies, cross-sectional observational studies, longitudinal observational studies, prospective randomized controlled trials, and other experimental studies, were evaluated for inclusion in this systematic review.

A variety of behavior therapies ranging in complexity from simple advice offered by a physician or other healthcare provider or a much more extensive therapy have been shown to be efficacious for tobacco smoking cessation. The success rate for abstinence from smoking increases when behavioral therapy is combined with pharmacotherapy. A behavioral intervention involves discussion, encouragement, advice and other modalities to help to achieve behavioral change19.

Group therapy is defined as the process of giving and receiving assistance, from individuals with similar conditions or circumstances, to achieve recovery in a group form. The group of people in group therapy voluntarily gather to receive support and provide support by sharing knowledge, experiences, coping strategies, and offering understanding towards smoking cessation intervention. The most common behavioral intervention for smoking cessation was individual therapy. Individual therapy is a face-to-face session with a trained therapist that focuses on behavioral change, which also incorporates motivational interviewing27. The individual intervention involves self-exploration and identifying ambivalence so that resolutions can be determined for effective behavioral change28.

Strategies for helping smokers to quit include behavioral counselling to enhance motivation and to support attempts to quit and pharmacological intervention to reduce nicotine reinforcement and the withdrawal symptoms of cessation of tobacco use29. We have included all the studies that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We evaluated the studies included in the systematic review by looking at the nature of behavioral support provided such as motivation to quit smoking, mode of delivery of the behavioral support, behavioral intervention service provider, and presence and type of pharmacotherapy provided.

The study domain was behavioral intervention (group therapy) for the treatment of nicotine addiction secondary to cigarette smoking. The outcome measure was abstinence from smoking following different types of behavioral interventions with or without pharmacotherapy. Abstinence was defined as not smoking for 3 to 6 months from the quit date. The results of the systematic review are reported following both the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)30 and the International Prospective Register of Systematic Review (PROSPERO)31 guidelines. Articles were excluded if other forms of tobacco were involved, such as chewing tobacco, electronic devices such as e-cigarettes, and other drug use such as cannabis.

Various study designs selected including systematic reviews, qualitative studies, cross-sectional observational studies, longitudinal observational studies, prospective randomized controlled trials, and other experimental studies, and the intervention effect (group therapy for smoking cessation) was measured by before and after treatment estimates that provided important information on the outcome. Review Manager (RevMan) software (version 5.4, Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, Cochrane Collaboration) was used for data analysis32. We used the random-effects model. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the I2 test. An I2 value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values show increasing heterogeneity (75% or greater considered substantial heterogeneity).

RESULTS

After the screening we identified a total of 300 articles for review (Figure 1). They were assessed for eligibility by checking against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, leaving 9 articles for the final systematic review. The selected journals were studies conducted in Asian countries, published in English, with full-text article available. All the selected studies for this systematic review fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Table 1 shows that the nine studies in the systematic review were in middle- and high-income Asian countries (Malaysia, India, China, Taiwan, Iran, Mongolia, Pakistan, Japan, and South Korea)6,14,24,33-38. Five studies were conducted in healthcare centers with smoking cessation clinics, three at universities, and one at a factory (a workplace intervention). The original authors were contacted to obtain further information for studies where details related to the systematic review were missing. There were three observational qualitative studies, two prospective cohort studies, two cross-sectional studies, one non-randomized quasi-experimental study, and a single cluster-randomized, controlled trial. The type of intervention (pharmacotherapy + behavioral therapy, pharmacotherapy only, behavioral therapy, or no intervention) varied between the selected studies. Six studies provided pharmacotherapy and behavioral intervention and three provided behavioral support. Four studies described using pharmacotherapy (nicotine replacement therapy) and behavioral therapy, and only one study described the use of bupropion. Behavioral therapy only, was provided in three studies. The studies included in the systematic review included smokers who smoked at least one cigarette per day with a mean of 10–22.1 cigarettes smoked per day, and low to high level of nicotine dependence. (Figure 1).

Table 1

Summary of the data extracted from articles identified in systematic review comparing group and other smoking cessation interventions services among Asian countries

Figure 1

Flow chart of search strategy results of electronic database search which include Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO, Ovid Medline from years 2004–2020

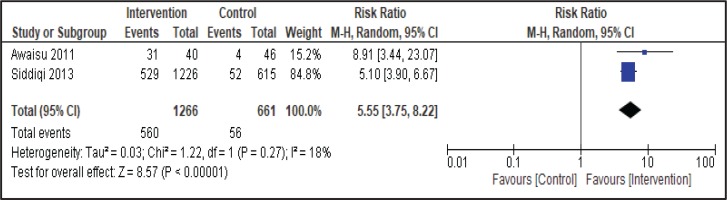

Two studies involving group therapy as behavioral intervention in the smoking cessation treatment compared outcomes with usual care practice. In a pooled analysis of these studies using the random-effects model, the intervention group significantly increased the abstinence rate (Figure 2). A total of 560 of 1266 (44.2%) patients who received intervention had quit smoking at 6 months compared with 56 of 661 (8.5%) patients who received usual care (RR=5.55; 95% CI: 3.75–8.22, p<0.001). In the study involving smokers who had tuberculosis and had undergone group therapy as smoking cessation behavioral support, the number of participants included in the final analysis was equal and comparable between the two groups. However, a heterogeneity analysis was conducted and there was no significant heterogeneity: I2=18% (p=0.27) (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Our review identified an important finding in the treatment for cigarette smoking for smokers in Asian countries. The availability of group therapy as an alternative to individual therapy (standard care) provides a treatment option for smokers to choose when a smoker decides to quit smoking. Furthermore, evidence has shown that group therapy provides better outcomes compared to minimal intervention or no intervention. Despite the evidence published in the western population, we found only a handful of articles relevant to our question of interest, which was the availability of group therapy for smoking cessation in Asian countries (Table 1). The studies looked at the use of group therapy in various circumstances such as group therapy + pharmacotherapy, counselling in the form of group therapy, and the treatment outcome.

Most of the studies selected in this systematic review were conducted in middle-income (Malaysia, Pakistan, India, Mongolia, Iran) and high-income countries (Japan, South Korea). In general, less wealthy countries have fewer resources to invest in smoking cessation than higher income countries. Despite this, smokers in poorer countries had no less interest in quitting smoking. Although smokers in middle-income countries were reported to have lower use of quit smoking medication and healthcare services, it does not translate to less interest in quitting. In Malaysia, smokers are keen to respond to healthcare queries on smoking behaviours7. This is important, because 80% of the world’s smokers are from low- and middle-income countries and it is estimated that 7 million deaths attributable to smoking will occur by 203015.

Huang et al.34 reported high abstinence, reduced number of cigarettes smoked and change in smoking behavior in group intervention with pharmacotherapy. Meanwhile, Siddiqi et al.36 found that group therapy alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy (e.g. bupropion) was effective. Sharifi et al.37 reported that counselling and pharmacotherapy can achieve smoking abstinence and reduction of the number of cigarettes smoked per day, as the smoking reduction was found to be a useful method for smokers who are unable to stop smoking immediately. Despite their potential among Asian smokers, group-based interventions for smoking cessation are under-researched. In other settings, studies have shown group-based treatment interventions to be effective. Group treatment that included medication such as varenicline, NRT, and bupropion, or bupropion + NRT, decreased the number of cigarettes smoked per day in a single group behavioral support39. Our results align with those of reviews in western nations, such as studies by Prochaska et al.40 and Schlam et al.41, in which behavioral support with pharmacotherapy increased cessation rates and improved long-term abstinence, but most smokers eventually relapsed.

Combining behavioral interventions such as counselling and pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation helps smokers in their quit attempt and the outcome is better than counselling alone, even if the counselling is provided by healthcare professionals. Behavioral support with pharmacotherapy increased cessation rates and improved long-term abstinence, but most smokers eventually relapsed42. There should be monitoring and supervision by healthcare professionals and the management should be collaborative work between doctors and nurses. Quit smoking initiatives at universities and workplaces have proven to be an effective setting for early quit attempts43 and should be explored in Asian nations. Employers should not only promote smoke-free workplaces and provide incentives to motivate smokers to quit smoking, but also introduce group counselling to help employees quit cigarette smoking.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite its potential and some evidence of benefit, research on group-based interventions for smoking cessation in Asian countries is lacking. Direct one-to-one comparisons between group therapy and individual therapy in behavioral support for smokers who want to quit smoking are needed. Innovative setting-based studies are also needed, such as those exploring the potential of workplaces and other group settings. Such evidence, based on the efficacy, affordability and feasibility of group therapy for smoking cessation among Asian smokers, would then support country-specific national guidelines to optimize country-specific and cost-effective smoking cessation initiatives. The practical implication identified in this systematic review on group therapy is that it can increase the likelihood of quitting cigarette smoking when the person is motivated in joining the group therapy. Group therapy can become a comprehensive extension of standard care available in most healthcare system. The impact of group therapy can become meaningful depending on the uptake so that the benefit of group therapy such as cost-effectiveness can be observed and documented. For research implications related to this systematic review, a larger number of participants in group therapy for smoking cessation would be desired to identify the impact of specific components in group therapy research and its efficacy.