INTRODUCTION

Globally, there were millions of confirmed cases of COVID-19, including more than 7 million deaths, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)1. Various risk factors for infection and severe outcomes of COVID-19 have been investigated2,3. Although smoking is a major cause of incident chronic diseases and premature death worldwide4, the effect of smoking status on COVID-19 outcomes is unclear. The low prevalence of current smoking among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 has been a consistent finding across most previous studies5-7. Previous studies demonstrated that past or current smoking was associated with higher odds of COVID-19 infection relative to never smoking8,9. A recent cohort study in England showed that former or current smokers were associated with a higher risk of death from COVID-1910. However, evidence for an association between smoking and death from COVID-19 has been mixed10-13.

The results from the meta-analysis were extracted from data on the ‘point prevalence’ of smoking status (i.e. assessment of smoking status at one particular time only). Since smoking behavior may change over time, repeatedly measuring information for smoking status within a specific period may be more reasonable14. Furthermore, the association between past smoking and death from COVID-19 may differ by smoking cessation period. Although evidence for the beneficial effect of smoking cessation on reducing the risk of death from COVID-19 may have significant implications during the COVID-19 pandemic, little is known about the association between smoking cessation and among patients with COVID-19. COVID-19 in Korea was primarily prevalent in specific regions (Daegu Metropolitan City, Gyeongsangbukdo) in the first half of 2020 and spread mainly in the metropolitan area and the whole country in the second half of 2020. During this study period, from January to May 2020, 11468 confirmed cases were reported. The distribution of characteristics such as sex and age among the study subjects included in this study was similar to that of the Korean population. This study investigated the association between smoking status and death from COVID-19 among patients with COVID-19 using nationwide cohort data.

METHODS

Data and participants

This study used data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), which is linked to information about the national health examination. The NHIS covers mandatory health insurance for all Korean citizens, and all insured individuals are required to have a standardized biennial health examination (an annual for manual workers). Since Korea has a single-payer national health system, the NHIS has all insured individuals’ demographic characteristics information (e.g. sex, age, household income, and residential area), results from national health screening (e.g. questionnaire survey on lifestyle, height, weight, and blood pressure measurements, and laboratory tests), all medical records regarding diagnoses, treatments, and prescribed drugs, and death information15. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) database have epidemiological information for all individuals who underwent laboratory SARS-CoV-2 tests and the information for results of SARS-CoV-2 test in KCDC data is linked to the NHIS database16.

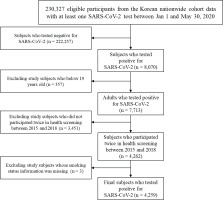

Among the 230327 individuals who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 from 1 January to 30 May 2020, this study eliminated subjects who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 (n=222257). This study also excluded participants aged ≤19 years (n=357) and eliminated study subjects who did not undergo a national health examination twice between 2015 and 2018 (n=3451). This study excluded subjects who had missing data for smoking status (n=3), and the final study sample included 4259 patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1).

Measures

The outcome of this study was death from COVID-19 among patients with COVID-19. The death information was ascertained from data of Statistics Korea and KCDC.

This study used information on smoking status surveyed from the self-reported questionnaire in the national health examination. The survey items regarding smoking status composed of current smoking, past smoking, and non-smoking. This study utilized information from the participants’ responses for two surveys on smoking status between 2015 and 2018 and study participants were classified into 4 groups: never smokers, recent quitters (≤2 years since smoking cessation), long-term quitters (>2 years since smoking cessation), and current smokers17.

Potentially confounding factors included sex, age, residential area, household income, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), fasting glucose, total cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and comorbidities. During the initial period in South Korea, there was an explosive outbreak of COVID-19 in the Daegu and Gyeongbuk regions18. Study participants were categorized into Daegu and Gyeongbuk regions and other regions. Household income was divided by the 5th quintile out of the total 20th quintile. BMI (kg/m2) was divided into groups as follows: 18.5 (underweight), 18.5–22.9 (normal weight), 23.0–24.9 (overweight), 25.0–29.9 (Class I obesity), and ≥30 kg/m2 (Class II obesity), based on the recommendation for Asian populations of the WHO19. Blood pressure was estimated once on the right arms of seated individuals who had rested for >5 minutes. Serum glucose levels and total cholesterol were measured by blood sampling after overnight fasting. eGFR was estimated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation for creatinine20. A history of hypertension (I10–15), diabetes mellitus (E10–14), dyslipidemia (E78), stroke (I60–63), ischemic heart disease (I20–25), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (J43–J44, except J430), chronic kidney disease (N18), cancer (C00-97), asthma (J45–J46), chronic liver disease (K704, K711, K713-K715, K721, K73, K743, K767-K769), and mental illness (F00-99) were confirmed by the reporting of at least 2 claims within 1 year during the 3-year period before the COVID-19 test using the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code21.

Statistical analysis

For patients with COVID-19, Pearson chi-squared test and ANOVA test were utilized to compare sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by smoking status. To explore the association between smoking status and the risk of death from COVID-19, this study used both current smoking and never smoking as the reference group, and multivariable logistic regression models with three incremental levels of adjustment as follows: Model 1: unadjusted; Model 2: adjusted for sex, age, household income, residential area, income level, and BMI; and Model 3: adjusted for all covariates.

All patient-related data were anonymized to ensure confidentiality. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University (7001988-202006-HR-917-01E) and the requirements for informed consent were waived because the NHIS data were established following anonymization by guidelines for rigorous confidentiality.

RESULTS

The general characteristics of study subjects who were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by smoking status are shown in Table 1. This study identified 309 current smokers, 236 recent quitters, 651 long-term quitters, and 3063 never smokers. The average SBP, DBP, fasting glucose, proportion of men, obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and chronic liver disease among the current smokers were higher than those observed among the never smokers. Conversely, the average eGFR, the proportions of older adults (≥60 years), those living in Daegu and Gyeongbuk, low household income, dyslipidemia, cancer, asthma, and mental illness among the current smokers were lower than those among the never smokers. Table 2 indicated the results for the association between smoking status and the risk of death from COVID-19 among patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. After adjusting for all potential confounding factors, current smokers (AOR=3.75; 95% CI: 1.23–11.36) and recent quitters (AOR=3.74; 95% CI: 1.12–12.53) were associated with an increased risk of death from COVID-19 compared to never smokers. There was no significant association between long-term quitters (AOR=1.22; 95% CI: 0.42–3.54) and death from COVID-19. Compared with current smokers, long-term quitters (AOR=0.33; 95% CI: 0.11–0.95) and never smokers (OR=0.27; 95% CI: 0.09–0.81) were associated with a reduced risk of death from COVID-19. There was no significant association between recent quitters (AOR=1.00; 95% CI: 0.30–3.35) and death from COVID-19.

Table 1

General characteristics of Korean patients who were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 from January to May 2020, by smoking status (N=4259)

Table 2

Association between smoking status and risk of Death from COVID-19 among Korean patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 from January to May 2020 (N=4259)

[i] Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: adjusted for sex, age, household income, residential area, and body mass index. Model 3: all covariates in Model 2 plus SBP, DBP, fasting glucose, total cholesterol, eGFR, and comorbidities. AOR: adjusted odds ratio. SBP: systolic blood pressure. DBP: diastolic blood pressure. eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

DISCUSSION

This nationwide cohort study investigated association between smoking status and death from COVID-19 among patients with COVID-19. This study found that current smokers and recent quitters were associated with an increased risk of death from COVID-19 compared to never smokers. Compared with current smokers, long-term quitters, and never smokers were associated with reduced risk of death from COVID-19. This study found that current smokers and recent quitters were associated with an increased risk of death from COVID-19 compared to never smokers. Simons et al.11 found that past smokers compared with never smokers were at increased risk of mortality among patients having COVID-19, whereas current smokers were not associated with risk of mortality. However, Patanavanich and Glantz12 showed that smoking was associated with an increased risk of death from COVID-19. Both of these studies are meta-analysis studies and methodological differences such as inclusion criteria of research data may attribute to conflicting results. Williamson et al.13, reporting from a large UK study, showed a decreased risk for death in current smokers compared with never smokers when fully adjusted, possibly indicating a Table 2 Fallacy and suggested a need to be clarified as the epidemic progresses and more data accumulate. The biological and inflammatory cascade that occurs upon SARS-CoV-2 infection may be particularly devastating for smokers22. Considering that significant association between recent quitters, but not long-term quitters, and death from COVID-19, there seems to be a possibility that the negative factors of smoking accumulated recently may be associated to fatal outcomes, and further research is needed.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this study may include potential selection bias because it included subjects who underwent two national health examinations between 2015 and 2018, thus approximately 55% of all adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 between 1 January and 30 May 2020. Second, information on smoking status was collected from a self-reported questionnaire, which is subject to recall and reporting bias. Since smoking status also changes over time, the smoking status measured in this study may differ from that at the time of the SARS-CoV-2 test. In addition, although this study divided individuals into recent and long-term quitters, the exact period of smoking cessation was not ascertained. Further studies are needed to investigate the associations according to the duration of smoking cessation. Third, since the percentages of current smokers (4.1% vs 16%) were significantly different between COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients23, it is necessary to take this into account in the interpretation of the results of this study. Furthermore, this study period was prior to: 1) the development of effective treatments; 2) a vaccine to reduce disease severity in those infected with SARS-CoV-2; and 3) the emergence of novel variants. All of these are likely to change the severity of disease once infected and have the potential to affect smokers, former smokers, and never smokers differently, particularly if, for example, vaccine uptake and health seeking behavior are very different between these cohorts. Finally, this study included only Korean adults, and further study is warranted to explore the associations in other ethnicities or countries.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated that current smokers and recent quitters were associated with an increased risk of death from COVID-19 compared to never smokers. Given the higher possibility of death in smokers who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 relative to never smoking, smoking is an independent risk factor for COVID-19. Furthermore, long-term quitters were associated with a reduced risk of death from COVID-19 compared with current smokers, suggesting the necessity of continuous smoking cessation among smokers or recent quitters to prevent the fatal risk of COVID-19.