INTRODUCTION

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are an electronic product consisting of 3 major components: a rechargeable battery, a smoke producing device, and an inhalation box1. The ingredients of inhalation mainly consist of edible glycerol, edible propanediol, edible propanetriol and edible essential oils2. Compared to combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes have no tar, nicotine, or carbon monoxide in inhalation. Therefore, the initial purpose of e-cigarettes is to help smokers or nicotine dependents quit smoking and reduce organ damage caused by smoking3. To obtain a more realistic feeling as if smoking combustible cigarettes, different proportions of nicotine are added to e-cigarettes4. In addition, a plethora of design features have led to an increase in smoking e-cigarettes among youth5. However, e-cigarette use may be related to other substances6,7. Ingredients of smoke produced by e-cigarettes may not only injure the lung but also can enter the circulatory system via gas exchange in alveoli, thus inducing cardiovascular risk8,9.

Stroke, as a common cerebrovascular disease, has a high mortality and disability rate. Although many studies have reported that using e-cigarettes was associated with occurrence of stroke, some studies have concluded that e-cigarettes may help smokers stop using combustible cigarettes and reduce the risk of stroke10,11. Therefore, we aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical epidemiology studies that assessed the association between stroke and e-cigarette use.

METHODS

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed referring to the protocol published in the database of International Platform of Registered systematic review and Meta-analysis Protocols (INPLASY, https://inplasy.com/, registration number: INPLASY202180086, DOI number: 10.37766/inplasy2021.8.0086.)

Search strategy

Literature search was performed in three public electronic databases of PubMed, Embase and Cochrane. The strategy of literature search is available in the Supplementary file.

Data extraction

Before data extraction, the quality assessment of included articles was performed via the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale Cohort Studies (NOQAS-CO) for cohort studies, Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale Case-control Studies (NOQAS-CA) for case-control studies, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for cross-sectional studies. For studies with the same quality assessed by the above evaluation standards, studies with larger number of included patients were considered to have higher quality. Under the premise that e-cigarette use was an independent exposure factor, all the data used to assess risk degree of stroke occurrence were extracted, including hazard ratio (HR), risk ratio (RR) in a prospective observational study, and odds ratio (OR) in a retrospective observational study. In addition, some confounders, which might result in errors, were adjusted, including gender, age, solutions of combustible cigarette smoking and e-cigarette use, definition of endpoints, period of observation, and other factors.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria were: 1) language, region or publication year, were not restricted; 2) clinical epidemiological studies included a cross-sectional study, a case-control study, and cohort study; 3) exposed group and non-exposed group differed in e-cigarette use; 4) baseline characteristics were not statistically different between exposed group and non-exposed group; 5) endpoint of observation was stroke; 6) a complete analysis of the outcomes of cohort studies was performed. Exclusion criteria were: 1) duplication; 2) reviews, comments, letters, case reports, protocols, notes and conference papers; 3) animal experiments; and 4) contents of articles that were irrelevant to this meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis

Relative numbers and their 95% confidence intervals were used to describe count data. Meta-analysis was performed using corresponding modules in Software for Statistics and Data Science (Stata, version 15.1; College Station, Texas 77845 USA). The pooled effect with 95% CI was calculated by a random effects model. I2 was used to test for heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the stability of overall results by recalculating the pooled effect of the remaining studies after omitting the study with the highest quality or the random effects model was switched to fixed effects model. Funnel plot symmetry or Egger’s regression was used to evaluate publication bias. To reduce heterogeneity, we recalculated the pooled effect of the remaining studies after omitting the study with the lowest quality or perform subgroup analysis directly. All p values were two-sided with a significance level set at 0.05.

RESULTS

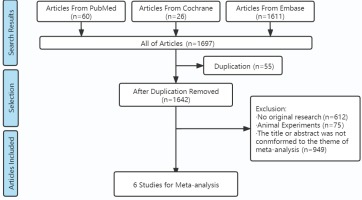

Totally, 1697 articles were retrieved from 3 databases according to the search strategy. After further screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 6 articles11-16 of cross-sectional studies were finally included (Figure 1). There were 1134896 participants in the 6 included studies (Table 1). The age range was 15–78 years. Males were close to 50%. Periods of observation were from 1 to 4 years. Different solutions of combustible cigarette smoking and e-cigarette use could be classified into 6 types: 1) neither e-cigarette nor combustible cigarette use; 2) currently e-cigarette use only but formerly combustible cigarette use only; 3) combustible cigarette use only; 4) e-cigarette use only; 5) both of e-cigarette and combustible cigarette use; and 6) solutions of combustible cigarette smoking and e-cigarette use were not separated, including 2), 4) and 5). Thus, different data were extracted from the same article. One study (2021 Reynolds) divided the type 6) solution into 3 sub-solutions: 1. Frequency of e-cigarette use > frequency of combustible cigarette smoking, 2. Frequency of e-cigarette use < frequency of combustible cigarette smoking, and 3. Frequency of e-cigarette use = frequency of combustible cigarette smoking, which produced 3 data extractions. One study (2021 Bricknell) divided the type 4) solution into 3 sub-solutions: e-cigarette use only every day, e-cigarette use only sometimes, e-cigarette use formerly.

Table 1

Characters of studies included

Because all the articles were cross-sectional studies, only AHRQ was used to assess their quality. One study (2019 Osei) was assessed as ‘Yes’ in every section, which had the highest quality (Table 2). In subjective influence section, one article (2020 Sverre) was assessed as ‘No’. Five articles were assessed as ‘No’ in the quality assurance section. In the data missed section, two articles were assessed as ‘No’. All the studies were assessed as ‘No’ in the follow-up section. Finally, one article (2020 Sverre) was assessed to have 6 ‘Yes’, which had the lowest quality. Only ORs directly appeared in articles, which were extracted by us to perform the next stage of data analysis.

Table 2

Quality assessment of studies via Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

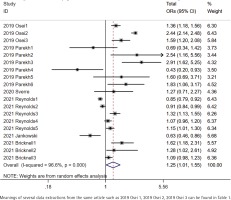

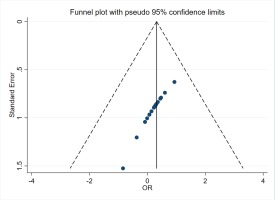

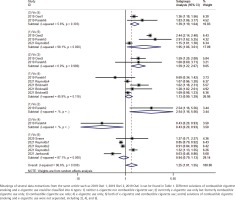

The total pooled OR was 1.25 (95% CI: 1.01–1.55) with heterogeneity of I2=96.6% (p<0.001) (Figure 2). In the sensitivity analysis, after omitting the study with the highest quality (2019 Osei), pooled OR was 0.99 (95% CI: 0.96–1.04) with a heterogeneity of I2=83.4% (p<0.001). There was a symmetrical distribution in the funnel plot (Figure 3). The study with the lowest quality (2020 Sverre) might have resulted in the high heterogeneity of total pooled OR; after omitting this study, the pooled OR was 1.23 (95% CI: 1.19–1.28) with a heterogeneity of I2=96.8% (p<0.001). However, heterogeneity was still high. Referring to combined combustible cigarette smoking and e-cigarette use, we performed subgroup analysis of total ORs. Compared to neither e-cigarette nor combustible cigarette users, pooled OR of stroke occurrence in current e-cigarette only users was 1.13 (95% CI: 0.99–1.29) (I2=45.9%, p=0.116). Compared to combustible cigarette only smokers, pooled OR of stroke occurrence in dual e-cigarette and combustible cigarette users was 1.39 (95% CI: 1.19–1.64) (I2=5.6%, p=0.303). In addition, pooled OR in currently e-cigarette only users who were formerly combustible cigarette only smokers was 1.59 (95% CI: 1.22–2.07) (I2=0.0%, p=0.989). Compared to neither e-cigarette nor combustible cigarette users, pooled OR of stroke occurrence in e-cigarette users who did not clearly distinguish the use of combustible cigarettes was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.79–1.13) and pooled OR in both e-cigarette and combustible cigarette users was 1.95 (95% CI: 1.06–3.61) with a heterogeneity of I2=87.1% (p<0.001) and I2=98.1% (p<0.001) (Figure 4). Compared to combustible cigarette only smokers, only one OR of stroke occurrence in e-cigarette only users was 0.43 (95% CI: 0.20–0.93). Compared to neither e-cigarette nor combustible cigarette users, pooled OR in current e-cigarette only users who were formerly combustible cigarette only smokers was 2.54 (95% CI: 1.16–5.56).

DISCUSSION

Our results of total pooled OR showed that the role of e-cigarettes as a risk factor for stroke is inconclusive due to the strong effect of prior tobacco use. However, publication bias and the data from the study with the lowest quality were not the source of significant heterogeneity. Finally, results in subgroup analysis support that one source of heterogeneity was the ambiguous solutions of combustible cigarette smoking and e-cigarette use. Moreover, due to the specific limitations of the cross-sectional study, we could not judge the causal and chronological ordering relationship of e-cigarette use and other risk factors of stroke occurrence such as hypertension, diabetes, auricular fibrillation, which might be other sources of heterogeneity. Compared to combustible cigarette only use, current e-cigarette only users with formerly combustible cigarette only smoking would face the risk of stroke occurrence, which might confirm that e-cigarette use as a replacement or adjunctive therapy for quitting smoking, could not reduce the risk of stroke occurrence. However, compared to neither e-cigarette nor combustible cigarette users, e-cigarette only use might not be the risk factor for stroke occurrence.

Smoke produced by e-cigarettes could injure the blood-brain barrier17,18 and lead to neuroinflammation19. In addition, e-cigarette exposure could influence cognitive functions20 and decrease brain glucose utilization in ischemic stroke20, which might lead to an unfavorable prognosis for stroke patients. We considered that blood vessel endothelia had been damaged via smoking combustible cigarettes. E-cigarette use might further deteriorate the injury of cerebrovascular endothelium in current e-cigarette users who smoked combustible cigarettes currently or formerly. Although e-cigarette only use might not be the risk factor for stroke, it might be associated with other diseases such as cancer, heart and lung diseases21,22. Therefore, the better choice for quitting smoking or nicotine might be to immediately stop using e-cigarettes and smoking combustible cigarettes, which might be a better way to reduce organ injuries.

Limitations

The major limitation of our study was that although there were sufficient data from 6 studies, the quality of the data could have been higher. Second, stroke as the definition of endpoint covers a wide range. Subtypes including transient ischemic attack, hemorrhagic stroke, and ischemic stroke could not be clearly separated. In addition, only ORs were extracted, which were of lower quality to explain causal relationships. Cohort studies that include e-cigarette users with no history of tobacco use are needed to confirm if e-cigarettes are an independent factor for stroke, an assessment which cannot be currently made.