INTRODUCTION

Chinese Americans are the largest Asian group in the US. It is one of the most rapidly growing ethnic groups in the US1. Accounting for 23% of the Asian American subpopulation, Chinese Americans numbered approximately 4 million in 20101. Most of the Chinese Americans reside in the state of California, with nearly 1.5 million in 2010, which is a 30% increase in population from 2000 to 20101.

Chinese immigrants are the largest group among Chinese Americans2. Of those who identify themselves as being Chinese American, the majority (69%) are immigrants, and the rest (31%) are American-born3. In 2013, Chinese immigrants accounted for 5% of all new immigrants to the US4. Since 1980, the population of Chinese immigrants in the US has grown nearly seven-fold, reaching almost 2.5 million in 2018, or 5.5% of the overall foreign-born population5. Although some cancer research involving Chinese immigrants has been done, most aggregated Chinese Americans, other Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders into one single group (AANPI), or integrated Chinese immigrants and native-born Chinese Americans into one group, potentially masking important subgroup and regional differences among specific Asian subgroups1,6.

In the US, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death7. It is also the most common cause of cancer death among Chinese Americans and is the second and fourth most common cancer among US Chinese men and women, respectively8. Lung cancer accounted for approximately 30% of all cancer-related deaths in Chinese Americans9.

Smoking cessation and lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography are two efficient methods to decrease the mortality rate of lung cancer. Compared to chest X-rays, lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography can significantly reduce the mortality rate of lung cancer by 20%10,11 and increase patients’ five-year survival rates from 15% to 52%12. Since 2013, the US Preventive Service Task Force has recommended certain high risk populations to receive low-dose computed tomography to screen for lung cancer13. From 2015, both private and public health insurances began to cover lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography for eligible populations, with physicians’ order and shared decision-making documents14,15. However, given the changed landscape of insurance coverage, the use rate of lung cancer screening remains low among the US eligible population. The percentage of eligible population who received lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography only increased from 3.3% in 2010 to 3.9% in 201516. Although no study has reported the rate of lung cancer screening among Chinese Americans or Chinese immigrants, it appears that the rate of lung cancer screening is low among these populations.

Cigarette smoking is a major cause of lung cancer17, which contributes to 87% of all lung cancer related deaths among the US population, with a mortality rate of up to 90% in males and 65% in females18. Since 1995, smoking has been banned in all enclosed workplaces in California; in 2012, restriction of smoking in residential dwelling units was passed and written into California law19. In the US, since 2009, a total of 30 states have enacted laws that require 100% smoke-free workplaces and/or restaurants and/or bars20. Chinese immigrants, who immigrated from a country with a socioculture context accepting tobacco use, to the US, a country with a socioculture context not accepting tobacco use, may change their smoking behavior after immigration, with their social environment after immigration playing a key role21.

As the primary and secondary prevention methods of lung cancer, smoking cessation and lung cancer screening with computed tomography, respectively, are important components for lung cancer intervention programs. Investigating Chinese immigrants’ smoking behavior change and exploring their perceptions of lung cancer screening could potentially help healthcare providers to design culturally tailored lung cancer screening and smoking cessation programs to decrease the mortality rate of lung cancer among this population.

To date, studies about Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening and smoking behavior change are limited. Since the evidence-based effective lung cancer screening and smoking cessation are widely recommended, an understanding of Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening and smoking behavior change is essential. The purpose of this systematic review was to investigate Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening as well as to explore the factors/barriers associated with their smoking behavior/cessation. This study will provide insights into evidence related to Chinese immigrants’ lung cancer screening and smoking behavior change. It will help to decrease the morbidity and mortality of lung cancer among this population.

METHODS

A systematic review design with narrative method was used. Electronic literature databases, including PubMed, CINAHL and Google Scholar were searched. Studies were selected if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) peer-reviewed; 2) focused on perceptions of lung cancer screening or smoking behavior change among Chinese immigrants in the US; and 3) published in English. Studies were excluded if they were: 1) not targeted at Chinese immigrants in the US; and 2) informal articles (e.g. letter to editors, commentaries, etc.) without data support. The following keywords were used to identify potentially eligible studies: lung cancer screening, low dose computed tomography, low dose CT, LDCT, Chinese immigrants, smokers, perception, knowledge, attitude, belief, perspective, smoking, smoking behavior, barriers, factor, and smoking behavior change. Equivalent index terms and free-text words were also used. The titles of the studies were filtered first, then the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied for further selection and finally the abstracts and texts were inspected. Features, including purpose, design, sample, setting, methods, results, discussion, and limitations were extracted from each study. Procedural rigor and methodology were considered for each study design.

RESULTS

Studies selection

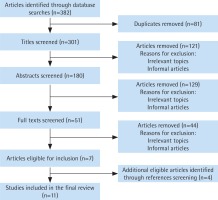

Initially, 382 references were retrieved from the databases, after adjustment of repeated articles and inspection of abstract and text, a total of 11 articles were selected to be included in the study (Figure 1). Results in the study were reported following the PRISMA approach (Supplementary file)22. Given the heterogeneity of the descriptive characteristics, purpose and outcome measures in the studies, the included studies were synthesized using a narrative approach.

Data evaluation

The methodological rigor of the included articles was evaluated using Bowling’s checklist23 for quantitative studies and the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist24 for qualitative studies. Bowling’s checklist is a systematic appraisal tool to evaluate a study’s clarity of aims, objectives, methods and appropriateness of data analysis. It provides a comprehensive checklist of 20 evaluation criteria rather than a scoring system to assess the quality of quantitative studies. The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist was used to assess the quality of all the included qualitative studies. All 11 studies had limitations, e.g. none of the articles discussed generalizability of findings to other populations. The methodological critique appraisal process was reviewed by the authors independently. Disagreements were reconciled by mutual agreement.

Study characteristics

For the 11 studies included in this review (Table 1), five were cross-sectional survey studies25-29, two were qualitative studies30,31, one was a secondary data analysis study32, one was a mix-method study33, one was a longitudinal observational study34 and one was a randomized control study35. The publication year of the studies were from 200225 to 201731. The sample size ranged from 2630 to 324932.

Table 1

Study characteristics for the included studies

| First author | Year | Design | Sample | Identified factors/barriers related to smoking behavior/cessation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yu et al.25 | 2002 | Cross-sectional survey study | 644 Chinese Americans | Age Education level Knowledge level about early cancer warning symptoms and signs Social environment Whether to use a non-Western clinic or physician for health care |

| Fu et al.26 | 2003 | Cross-sectional survey study | 541 Chinese American adults (aged≥18 years) attending four pediatric, medical, or dental practices located in Philadelphia’s Chinatown | Acculturation English language proficiency level Gender |

| Ma et al.27 | 2004 | Cross-sectional survey study | 1374 Chinese Americans | Acculturation Gender |

| Shelley et al.28 | 2004 | Cross-sectional survey study using in-person, household-based interviews | 712 Chinese Americans | Tobacco-related knowledge level Age Acculturation |

| Sussman and Truong29 | 2011 | Cross-sectional survey study | 364 first-generation immigrants living in New York City | Acculturation Gender Duration of residence English language proficiency level |

| Petersen et al.30 | 2016 | Qualitative study using in-depth dyadic and individual interviews | 13 immigrant smoker-family member pairs of Vietnamese (n=9 dyads, 18 individuals) and Chinese (n=4 dyads, 8 individuals) descent, including seven current and six former smokers and 13 family members | Lack of social support (e.g. self-isolation, the limited support systems in their community or work/school environments, the scarce or non-existent information about how to stop smoking) Commonality of smoking in their community |

| Saw et al.31 | 2017 | Qualitative study using focus group interviews | Seven focus-group interviews with 63 Chinese immigrants | Smoking cessation suggestions from healthcare providers Realized changes in environmental regulation Social acceptability of smoking after immigration Perceived benefits to improve children’s health and achieve family harmony Irritating odor Negative nonverbal reactions (e.g. people covering their noses and mouths) Environments with pro-smoking norms |

| Gorman et al.32 | 2014 | Secondary data analysis study | 3249 Latino and Asian American immigrants | Duration of US residence Connections with others (e.g. English language proficiency and citizenship acquisition) Psychological status (e.g. stress) Gender |

| FitzGerald et al.33 | 2015 | Mix-method study | Qualitative: 16 Chinese smokers participated in focus groups interview Quantitative: 167 current Chinese immigrant smokers (137 males and 30 females) | Education level Knowledge level of smoking consequences Age Language and literacy issue Wrong personal beliefs (e.g. they can quit on their own whenever they decide to; perceived minimal health risk of smoking; smoking relaxed them and helped them feel less stress) |

| Tsoh et al.34 | 2003 | Longitudinal observational study | 199 Chinese smokers who resided in northern California | Psychological status (e.g. depressive disorders, dysthymia) |

| Wu et al.35 | 2009 | A two-group experimental random design with baseline assessment and follow-up measures | 122 Chinese smokers | Limited resources for pleasure Lack of alternatives to smoking |

Perceptions of lung cancer screening

To date, there is a limited number of studies on the topic of Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening. However, among the US population, previous research has explored US general smokers’ perceptions of lung cancer screening and identified several factors that may influence high-risk US population’s behaviors related to lung cancer screening, including perceived low value of lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography, lack of knowledge about lung cancer screening, wrong beliefs (e.g. fatalistic beliefs), distrust of medical system, stigma (e.g. perceived blame and stigma associated with lung cancer and smoking), negative expectations of lung cancer screening (e.g. radiation exposure, false-positive results, over-diagnosis, procedure and diagnose-related anxiety or distress), inconvenience (e.g. lack of transportation, time constraints, and appointment conflicts), economic barriers (e.g. insurance coverage), demographic barriers (e.g. age, gender, smoking history), instrumental barriers (e.g. concerns about accuracy of low-dose computed tomography, uncertainty regarding the benefit of lung cancer screening, acceptance level of trial evidence and guidelines, and concerns about the procedure), infrastructural barriers (e.g. insufficient identified screening centers and personnel, lack of an active low-dose computed tomography screening program and equipment), and lack of information from healthcare providers36-44.

Although reports about Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening are lacking, previous studies conducted among Chinese immigrants showed multiple perceptual barriers existed toward cancer screening45, which may present in their perceptions of lung cancer screening as well. Some Chinese community residents were not familiar with the preventive measure of cancer screening and had not received common cancer screening before45. In addition, language barriers and cultural influence (e.g. ‘yin and yang’, ‘qi’) had a negative impact on Chinese immigrants’ perceptions toward cancer screening behaviors46. Misconceptions about cancer screening were also widespread among Chinese immigrants (e.g. screening for cancers can lead to cancers)45.

Smoking behavior change among Chinese immigrants

China has the largest number of smokers in the world47. It has more than 50% of adult male smokers47. In contrast to smokers in China, the rate of smoking prevalence among Chinese immigrants is much lower. There is evidence that immigration may lead to a reduction in smoking48-50. In some studies, Chinese men outside their original country have been labeled ‘model’ immigrants in smoking reduction or cessation after migrating to a region or country with low smoking rates51. A study with Chinese immigrants in California identified that 52.5% of Chinese smokers had quit smoking and remained abstinent for one year51. Although this quit level was comparable to the quit rate for California smokers in general (53.3%), the quit rate among Chinese immigrants was about seven times the quit rate among smokers in China51. Similar findings were also reported in other studies. Results showed Chinese immigrant smokers tend to reduce their smoking more than other subpopulations in the US48,52.

Interestingly, as the duration of US residence became longer, smoking among Asian immigrants (including Chinese immigrants) increased in both prevalence and frequency, despite the context of a smoke-free policy in the US32, which was notable among female immigrants53. Previous research has found that immigrants with longer US residence or greater acculturation to US society have worse health and risk factors (e.g. smoking prevalence) than those with shorter residence or less acculturation53,54.

Factors influencing Chinese immigrants’ smoking behaviors

Previous studies have identified various sociocultural factors, including cultural beliefs, lack of cancer awareness and education, which may lead to higher rates of smoking among immigrant populations55. Among Chinese immigrants, results showed factors related to personal characteristics, psychological status, acculturation, and cues from external environment that may influence their smoking behaviors.

Personal characteristics

Personal characteristics, including age, level of education, gender, knowledge level about early cancer warning symptoms and signs, English language proficiency level, whether to use a non-Western clinic or physician for healthcare, and duration of residence, were significantly associated with Chinese immigrants’ smoking attitude and smoking behavior25,26,29. According to Shelley et al.28, possessing a high level of tobacco-related knowledge and being aged ≥35 years predicted smoking cessation behavior among Chinese Americans. Both were positively associated with the smoking cessation behavior28. These results may potentially be also generalized to Chinese immigrants. Also, current smokers relative to former smokers were more likely to be recent immigrants and to be from mainland China28. A study also showed that higher education and better knowledge of smoking consequences contributed to having a greater intent to quit smoking among Chinese immigrants25. In addition, fatherhood may be positively associated with smoking cessation among Chinese immigrants31. Due to concern about the impact of smoking on the health of young children, being a father or prospective father prompted the Chinese smoker to quit or reduce smoking31. Furthermore, researchers found that, regardless of the amount of time spent in the US, immigrants who form strong local connections, evidenced by English language proficiency and citizenship acquisition, have increased rates of smoking cessation32.

Psychological status

Psychological status may impact Chinese immigrant smokers’ smoking behavior. Previous studies showed that Chinese American smokers, including Chinese immigrant smokers, reported higher depressive symptoms than Chinese Americans34. A higher rate of major depressive disorders (30.3%) and dysthymia (11.6%) during Chinese immigrants’ lifetime34 may influence their smoking behavior. Results showed that more stressed immigrants were more likely to smoke32. However, Asian women who immigrated to the US, including Chinese female immigrant smokers, tended to experience a higher increase in smoking after immigration compared with their male counterparts, given the decreased distress from smoking stigma in the changed culture context32.

Acculturation

Acculturation has a significant impact on Chinese immigrants’ smoking behaviors27. While more acculturated male adults were less likely to smoke than the less acculturated male adults, less acculturated adult females and youth were less likely to smoke than the more acculturated females and youth27. Overall, Chinese immigrant males were more likely to smoke than Chinese immigrant females regardless of acculturation status27. Furthermore, acculturation was positively associated with never smoking among men but not associated with smoking cessation28. While male Chinese American including Chinese immigrant ever smokers were less acculturated relative to never smokers, acculturation was not related to current versus former smoking status28.

Cues from external environment

Cues from external environment, including social and cultural acceptability of smoking, may influence Chinese immigrant smokers’ smoking behavior. A qualitative study conducted by Saw et al.31 among Chinese-speaking smokers and non-smokers in California showed that factors influencing their intention of smoking cessation included smoking cessation suggestions from healthcare providers, realized changes in environmental regulation, social acceptability of smoking after immigration, perceived benefits to improve children’s health and achieve family harmony, and irritating odor. According to Saw et al.31, both smokers and non-smokers in the US were aware that smoking in public was not viewed favorably. Several smokers reported that their smoking behaviors sometimes met with negative nonverbal reactions (e.g. people covering their noses and mouths)31. Due to such external nonverbal reactions, one smoker reported quitting smoking, and others reported decreased cigarette consumption31. Furthermore, non-smokers noted that their smoking household members reduced or quit smoking after immigrating to the US, and several stated that visiting China had resulted in relapsing or increasing the smoking intensity31.

Barriers to smoking cessation among Chinese immigrant smokers

Language barrier

A previous study showed that language and literacy issues were a barrier for Chinese immigrant smokers to access smoking cessation information and to obtain useful information from social media33. Older Chinese immigrant smokers (aged ≥35 years) mentioned that they had limited exposure to public sources of information on cessation services in their native language33. Younger Chinese immigrant smokers (aged <35 years) mentioned lacking disseminated messages in their native language related to smoking cessation and quitting services through social media (e.g. text messaging)33.

Unwillingness to use smoking cessation assistance methods

A study showed Chinese immigrant smokers rarely used smoking cessation aids or services after immigrating to the new country, despite both ex-smokers and current smokers had reported making more than one quit attempt30. Few Chinese immigrant smokers reported taking or being advised to take medications (e.g. patches or nicotine gum) to aid in smoking cessation31. Barriers to seeking smoking cessation assistance services among Chinese immigrant smokers may derive from two aspects, firstly practical barriers, which include lack of available information on smoking cessation assistance and difficulty in accessing smoking cessation assistance, and secondly cultural barriers, which include denial of physiological addiction to nicotine, mistrust in the effectiveness of smoking cessation assistance, tendency of self-reliance in solving problems, and concern of privacy revelations related to utilization of smoking cessation assistance30.

Healthcare environment’s insufficiency to counter pro-smoking norms

Most of the Chinese-speaking smokers and non-smokers in California, including Chinese immigrant smokers, reported being unable to sustain smoking cessation32. Although they had tried to quit smoking when they were acutely ill and were advised to quit smoking by medical providers, once they were no longer sick, especially if they continued to socialize in environments with pro-smoking norms, they returned to smoking and rationalized their behaviors32.

Lack of social support

Chinese immigrant smokers reported lack of social support to quit smoking, including self-isolation and the limited support systems in their community or work/school environments, as well as scarce or non-existent information about how to stop smoking30,35. They reported the commonality of smoking in their community and limited resources for pleasure, as well as lack of alternatives to smoking, urged them to smoke and be linked to their peers30,35.

Wrong personal beliefs

Wrong personal beliefs, such as ‘they can quit on their own whenever they decide to’ and perceived minimal health risk of smoking hindered Chinese immigrant smokers’ smoking cessation behaviors33. In the study conducted among 167 current Chinese immigrant (137 males and 30 females) smokers, the main reasons of 62% of the participants to smoke regularly were the beliefs that smoking ‘relaxed them’ and ‘helped them feel less stress’33.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review explored Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening and identified the factors/barriers related to their smoking behaviors/cessation. It provides evidence for the development of lung cancer screening programs for Chinese immigrants30. The identified factors influencing Chinese immigrants’ smoking behaviors as well as barriers towards their smoking cessation behavior could potentially help to design culturally adapted smoking cessation intervention programs for Chinese immigrant smokers and facilitate the implementation of tobacco control policy both in the US and China.

Chinese immigrants’ smoking behaviors were influenced by multiple factors, including personal characteristics, psychological factors, and cultural factors (acculturation, external environment). Upon immigration, the smoking rate among Chinese immigrants became much lower than their counterparts in China, which is potentially due to the self-selection bias related to the Health Migration Effect56, or some combination of underdiagnoses of health conditions subsequent to immigration, lower susceptibility, healthier ingrained behaviors, or a likelihood of returning to their host country upon becoming sick57. However, with the duration of US residence becoming longer, smoking among Chinese immigrants increased in both prevalence and frequency32. Exceptionally, in the same study32, researchers also found that, immigrants who form strong local connections, such as English language proficiency and citizenship acquisition, benefit from reduced smoking regardless of the amount of time spent in the US. One possible reason for this is that the immigrants with higher English language proficiency and citizenship acquisition are less stressed and have higher socioeconomic standing32. Also, smoking behavior change among Chinese immigrants may be influenced by psychological factors and cultural factors. A stressful external environment related to the sociocultural change as well as smoking control policy restriction may influence Chinese immigrant smokers’ smoking behavior, e.g. Chinese female immigrant smokers usually experienced an increase in smoking after immigration. It may be possibly due to the psychological changes in culture context related to the decreased distress from smoking stigma among women32 and/or the sociocultural change that acculturated their smoking behaviors27.

Multiple barriers for smoking cessation exist among Chinese immigrant smokers. As a population who use Chinese as the first language, most of Chinese immigrants had low English language proficiency and low heath literacy58,59, which may impact their ability to get access to smoking cessation services, obtain information or resources about smoking cessation, receive support from social services or healthcare providers, etc. This may particularly be reflected by the low utilization rate of smoking cessation assistance methods among this population. Their ability to get access to the smoking cessation assistance services may be restricted by the language barrier. In addition, connections with the pro-smoking peers may hinder their smoking cessation progress and trigger smoking relapse thoughts. Lack of social support and wrong personal beliefs may also leave them battling smoking cessation unaided. To increase smoking cessation rates among this population, culturally tailored smoking cessation programs should be developed in the Chinese language with appropriate health literacy levels. Smoking cessation assistance services and social support should also be offered at the community level to help Chinese immigrant smokers to connect with necessary resources.

Limitations

There are some limitations in this review. First, data in this study were synthesized using a narrative method rather than a meta-analysis method. As such, our findings cannot be used to identify the specific relationships between smoking behavior change and various related factors. Second, we included studies only from peer-reviewed English-language journals, which may have restricted our findings and biased the data. Third, due to the scarcity of studies conducted on Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening, information provided in this study on this topic is limited as well.

Future research

To date, a limited number of studies have been conducted on Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening. Although we generally synthesized relevant findings about US population’s perceptions of lung cancer screening in this study, due to the cultural differences, future studies exploring Chinese immigrants’ perspectives of lung cancer screening are needed. No evidence was found about the relationship between comparative purchase cost of cigarettes in the US and Chinese immigrants’ smoking cessation. Although the economical/financial factor was always deemed as an important element influencing smokers’ smoking behavior, no study has been conducted on this topic among Chinese immigrants in the US. Future research is needed to explore Chinese immigrants’ smoking behavior change and the comparative purchase cost of cigarettes. Future research focusing on lung cancer screening and smoking behavior change among Chinese immigrants should address the changes in sociocultural context and language barriers for them accessing smoking cessation information. The tobacco culture which was cultivated in the long history of Chinese culture and the English language barriers may also hinder their use of lung cancer screening. Further exploration of Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening and smoking behavior change is necessary and essential for facilitating the use of lung cancer screening and smoking cessation among this population.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review summarized Chinese immigrants’ perceptions of lung cancer screening, factors influencing their smoking behavior change and barriers to their smoking cessation. It provided evidence and suggestions for facilitating lung cancer screening and smoking cessation programs among Chinese immigrants. Future research aiming to explore Chinese immigrants’ perspectives toward lung cancer screening are needed. Factors including individual’s personal characteristics, psychological status, acculturation and cues from external environment should be considered when smoking cessation programs are implemented. Language barriers, individual’s unwillingness to use smoking cessation assistance methods, healthcare environment’s insufficiency to counter pro-smoking norms, lack of social support, and wrong personal beliefs should be considered when smoking cessation consultations are given.